“I sailed away from N[üesch] with spectacular effect. Come and see me when you have time, I’ll tell you a good story.“

Albert Einstein to Conrad Habicht, February 4, 1902

EINSTEIN IN SCHAFFHAUSEN

At the beginning of September 1901, Einstein wrote to his former school friend Marcel Grossmann: “However, I am now also in the happy position of having gotten rid of the perpetual worry about my livelihood for at least one year. That’s to say that as of September 15 I will be employed as a private tutor by a teacher of mathematics, a so-called Dr. J. Nüesch, in Schaffhausen, where I’ll have to prepare a young Englishman for the Matura examinations. You can imagine how happy I am, even though such a position is not ideal for an independent nature. Still, I believe that it will leave me some time for my favorite studies so that at least I shall not become rusty.“

However, the one year which was mentioned in the letter, should only become four and a half months.

Schaffhausen, the northernmost canton of Switzerland, belongs to the northeast and east of Switzerland. The main place and at the same time the largest place of the canton is the city of Schaffhausen with the same name which had, at the time of Einstein, approximately 15,000 inhabitants. From Schaffhausen to Winterthur the distance is approximately 30 km, to Zurich approximately 55 km.

The Swiss pedagogue and prehistorian Dr. Jakob Nüesch (1845-1915) in August 1901 and per advertisement in the Schweizerischen Lehrer-Zeitung [Swiss Teacher Newspaper] looked for an assistant for his boys boarding house in Schaffhausen. Thanks to the recommendation of his former school friend Jakob Ehrat, Einstein got the position.

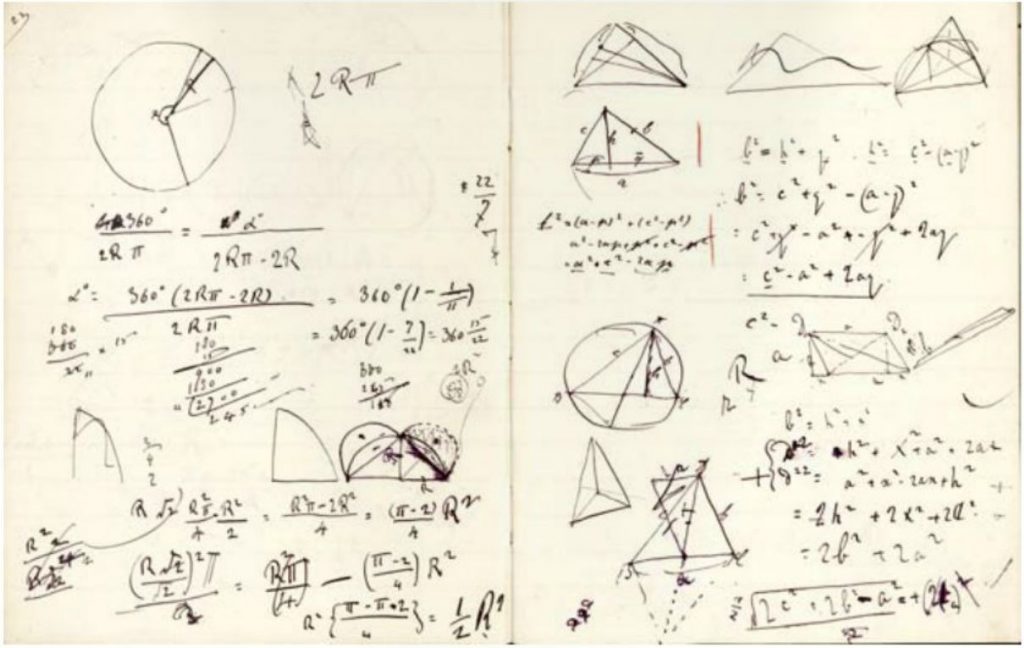

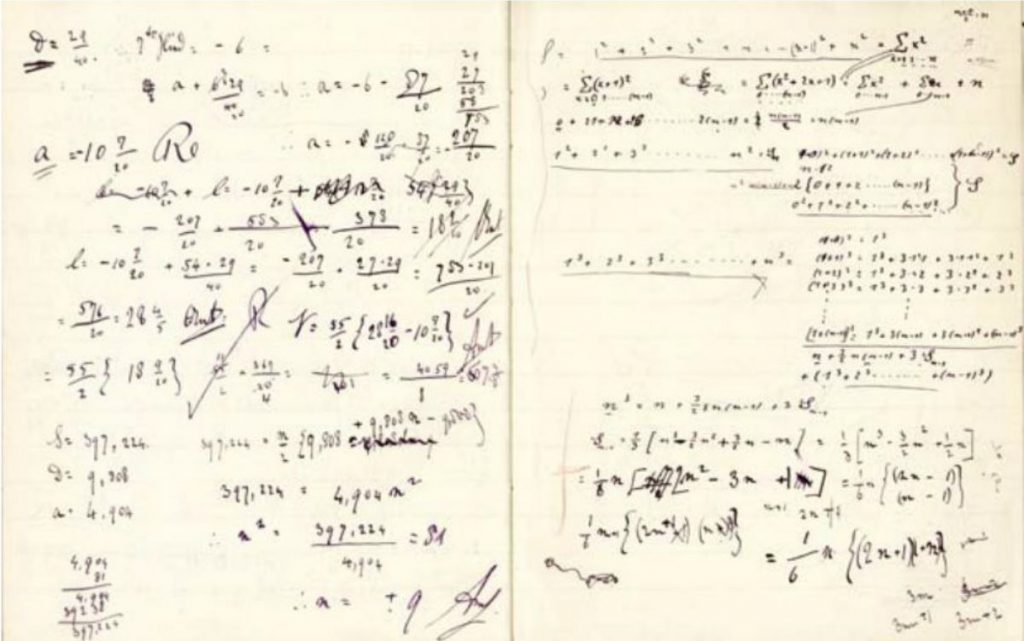

Coming from Winterthur, where he had been working at his dissertation for some time, Einstein came to Schaffhausen in the middle of September 1901. There he lived at first in Fulachstrasse 22 in the house of his employer Dr. Nüesch, who operated a private “Teaching and Educating Institution“. He was married, had three daughters, and one son. It was Einstein‘s task to prepare the nineteen year old Englishman Louis Cahen, who wanted to study Architecture at the ETH in Zurich, for the Matura. Teacher and student are told to have been on reasonable terms. Thus, the Einstein biographer Carl Seelig wrote: “However, on both sides, the learning and teaching eagerness seems to have been tempered.“ From this time, there are still two workbooks available which were corrected by Einstein, and which are filled with mathematical formulas and drawings. Today, they can be found in the city archive of Schaffhausen.

2, 3 workbooks of Louis Cahen – with notes of Einstein

After some weeks, Einstein no longer felt well in his lodging in Nüesch’s house. There more and more often were disputes and arguments between Einstein and Nüesch.

Einstein looked for another room and found it in Fulachstrasse 6 with the married teachers Cäcilia and Carl Baumer. With regard to his new room, Einstein wrote to Mileva on November 28: “It is very cozy in the new room, even though its only ornaments are myself and the dear red lampshade, …“

In the same letter it says: “I am living here as if I were completely alone, since I do not see anybody privately.“

In a letter to Mileva he wrote on December 12: “I therefore decided to set up myself here as comfortably as possible. I therefore went to N[üesch] and told him to give me the money the money for the meals, so that eventually I might save a little money. He said, a flush with rage, that he has to think about it. Then he conferred with his fine little spouse. When I returned in the evening, he was very snotty and told me, with an authoritative expression: ‚You know our conditions, there is no reason to deviate from them. You can be quite satisfied with the treatment you are getting.‘ And I said: ‚Very well, as you like, I have to give in for the time being. – I’ll know how to find living conditions that suit me better.’ (Imagine what nerve, in my position!) He understood that and softened up immediately. He noticed that I am less concerned with saving money than with not wanting to eat with him and his fine family, swallowed his rage, and told me as softly as he could: ‚Would you be satisfied if I arranged for your meals somewhere, in a restaurant?’ I immediately understood why he wanted that – so that it shouldn’t be possible to calculate how much he steals from the 4,000 fr. put out for me. So I happily agreed and took my leave, remarking that he should make the arrangements as quickly as possible, I had attained my goal, after all. They are now foaming at their mouths with rage against me, but I am now as free as the next man. […] Long live impudence! It’s my guardian angel in this world.“

As he also did not like the schoolmasterly idyll which was prevailing at the Baumer family, he looked for a new room in December. He found it in Bahnhofstrasse 102 above the restaurant “Cardinal“ where he lived until the end of his teaching position in Schaffhausen.

Einstein got along well with his student, despite his missing eagerness to learn. He even shortly thought about taking him with him to Bern later, to continue to teach him there. However, this plan did not become reality.

On December 18, 1901, Einstein had, through his former school friend Marcel Grossmann, applied for a job at the patent office in Bern.

In Schaffhausen, Einstein found no conversation partner with whom he had been able to talk about current topics of physics. However, he intensively dealt with physics. Thus, he wrote to Mileva on December 17, 1901: “I am now very eagerly working on an electrodynamics of moving bodies, which promises to become a capital paper.“ In 1905, this work finally led to the publication of his “special theory on relativity“. He also worked at his dissertation which he handed in at the University of Zurich in November 1901, but already withdrew it in February 1902.

With his friend Conrad Habicht who lived in Schaffhausen he had the opportunity to play the violin together, or to go to classical concerts, which he liked. To Mileva he wrote on November 28: “The evening of the day before yesterday the local music teachers organized an evening of chamber music, which was delightful beyond my expectations.“ On December 11, he even had the opportunity to play the violin at a subscription concert together with Habicht and the other members. His other friend in Schaffhausen, Jakob Ehrat, lived and worked in Zurich at this time.

To be able to be near to her beloved one, Mileva Maric stayed some days in Stein am Rhein, approximately 20 km away from Schaffhausen, in the hotel Steinerhof. Mileva expected her first child. Einstein, who was in love, tried to visit his pregnant girlfriend whenever it was possible. However, due to financial reasons this was not possible very often. Thus, Mileva wrote on November 13, 1901: “So now you are again not coming tomorrow! And you don’t even say: I am coming on Sunday instead! But you’ll surprise me then for sure, won’t you? […] But you really don’t have any money left? Very nice! You earn 150 fr., have bed and board, and don’t have a centime at the end of the month!“

Albert Einstein’s stay in Schaffhausen and his teaching position there ended before time at the end of January 1902.

In February, 1902, Einstein was 23 years old and came to Bern, where he took up a position as technical expert of the 3rd class at the Swiss office for intellectual property in June.

Illustrations Credits:

© Stadtarchiv Schaffhausen: 1, 2, 3

Schweizerisches Literaturarchiv (SLA), Bern: 4

Bibliography:

| Albrecht Fölsing | Albert Einstein. Eine Biographie | Frankfurt on the Main 1993 |

| John Stachel, u.a. | The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1 | Princeton 1987 |

| Carl Seelig | Albert Einstein. Eine dokumentarische Biographie | Zurich 1954 |

| Martin Cordes | Albert Einstein in Schaffhausen Begleitheft zur Ausstellung | Schaffhausen 2005 |

| Anna Beck, Translator Peter Havas, Consultant | The Collected Papers of Albert Einstein, Volume 1 English translation of selected texts | Princeton 1987 |

DEUTSCH

DEUTSCH